How to Choose a Chess Move: How masters really think

Eager to improve your chess? With this sneak peek from How to Choose a Chess Move by Andrew Soltis, publishing this July, dive into your next chess game with a newfound confidence and some secrets up your sleeve…

By Andrew Soltis

HOW MASTERS REALLY THINK

Tactics can be scary, especially when you see how a world-class player can fall victim like that. But you can become a good tournament player by relying primarily on general principles and elementary tactics.

Unless your opening leads you into a slugfest, you can look for principled candidates for most of a game. The rest will be relatively simple tactical moves. And when you do have to make a move based on calculation, you will rarely have to look more than two or three moves into the future.

A revealing insight into how a great player really thinks occurred when Garry Kasparov played a game against Internet opponents. Anyone could log on to a site and vote for the best move to play against Kasparov, then world champion.

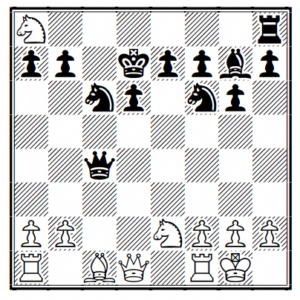

The 1997 game, dubbed “Kasparov versus the World,” began:

1 e4 c5 2 Ìf3 d6 3 Íb5+ Íd7 4 Íxd7+ Ëxd7 5 c4 Ìc6

6 Ìc3 g6 7 0-0 Ìf6 8 d4 cxd4

9 Ìxd4 Íg7 10 Ìde2 Ëe6

11 Ìd5 Ëxe4 12 Ìc7+ Êd7

13 Ìxa8 Ëxc4.

Kasparov visualized this position earlier, when he chose his 11th move. He planned to continue 14 Ìc3, a principled move. But when the position actually occurred he changed his mind. He explained his thinking in a book, Kasparov Against the World:

After 14 Ìc3 there would be no vulnerable targets for White to attack. That might not sound important. But once Black captures the trapped a8-knight, the middle game that follows could turn out very badly for White because he lacks a specific goal.

14 Ìb6+!

Kasparov chose this because it prompted a weakness on b6. He was using very general reasoning, not trying to calculate how he would actually attack that pawn. He

looked no further than 14…axb6. “I have to admit I didn’t know what to do next,” he said.

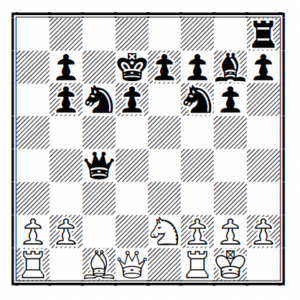

14 … axb6

He looked at 15 Ìc3 but he foresaw a problem. Black could prepare…b5-b4 and turn the weaklooking b-pawn into an aggressive asset.

So, Kasparov turned his attention to 15 a4. It would prepare Ìc3 when …b5-b4 would be harder for Black to carry out.

But Kasparov saw a problem with 15 a4. Black would have good replies such as 15…Ìd5 and 15…Ìe4. He switched his attention back to 15 Ìc3. Returning to a candidate you have already rejected was considered a sin by the celebrated Soviet trainers of Kasparov’s youth. But it was a sin widely committed.

15 Ìc3

In the end, Kasparov played this because of another change in his thinking. He realized his winning chances were not as good as he thought a few moves ago. He now felt 15 Ìc3 b5 might be the best position he could get.

Having an objective sense of what your chances are is very important in choosing the best move.

Taken from ‘It’s Your Move’ in How to Choose a Chess Move by Andrew Soltis. Out in July and available to pre-order now.